Better Rolled Hems

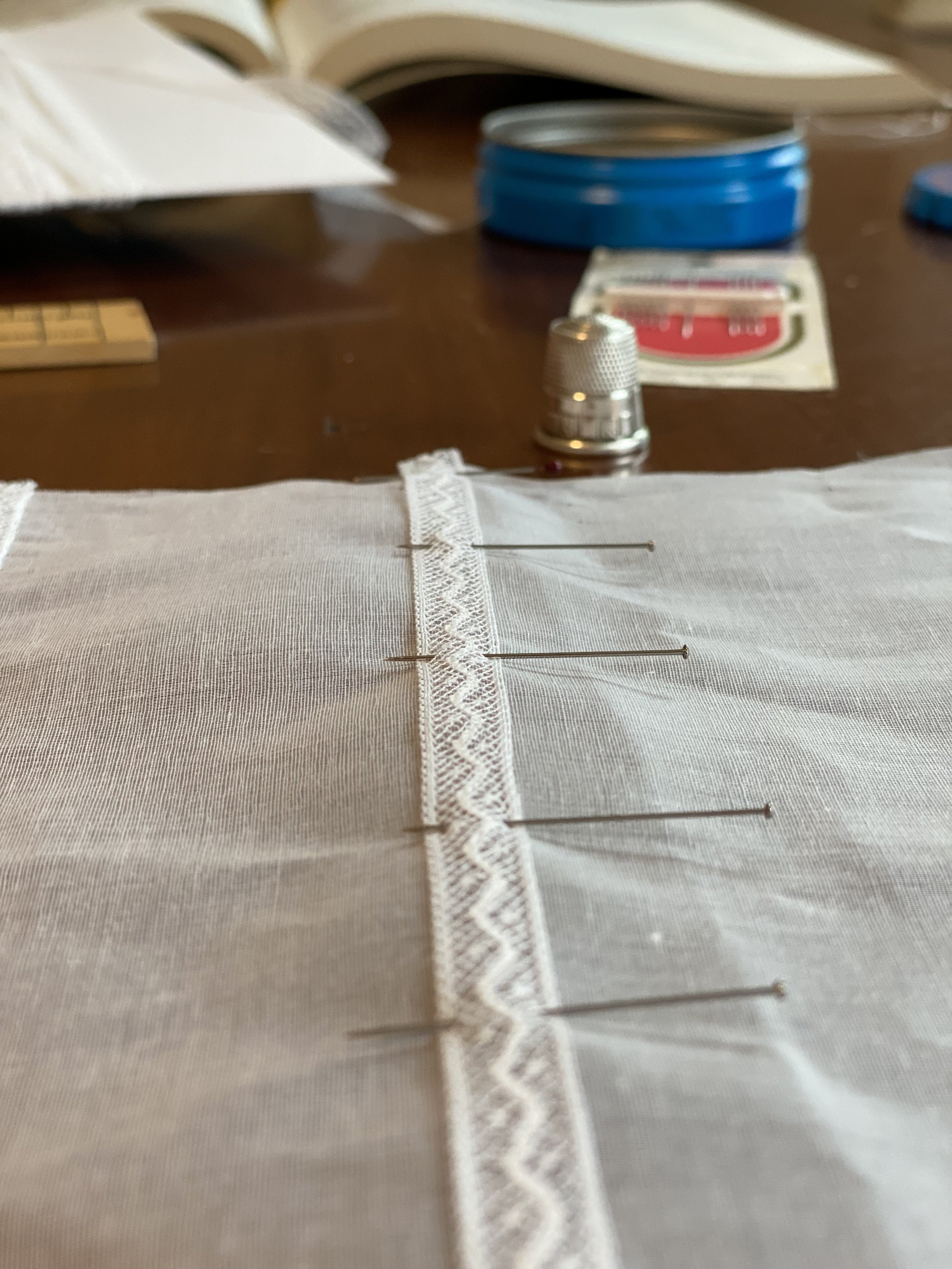

Rolled hems are delicate and beautiful. They make a great finish to a handkerchief or scarf. For 18th-century English sewing they were the foundation for millinery (accessories). I have noticed that beginners when trying to achieve a rolled hem will do a couple of things:

-they will not roll enough fabric into the hem to keep the raw edges encased.

-they will try to flatten the hem vs. keep it truly rolled and lofty.

You should have about 1/4”/6mm worth of fabric rolled up in your hem. Like this:

To avoid flattening your rolled hem practice your technique with these videos: