Following the Thread: Pulling Threads for Hand-Sewing

“See that the edges of the work are perfectly even before turning down, which should be done to a thread, unless the work is not cut straightwise.”

“The Workwoman’s Guide,” By A Lady, 1838. p. 1.

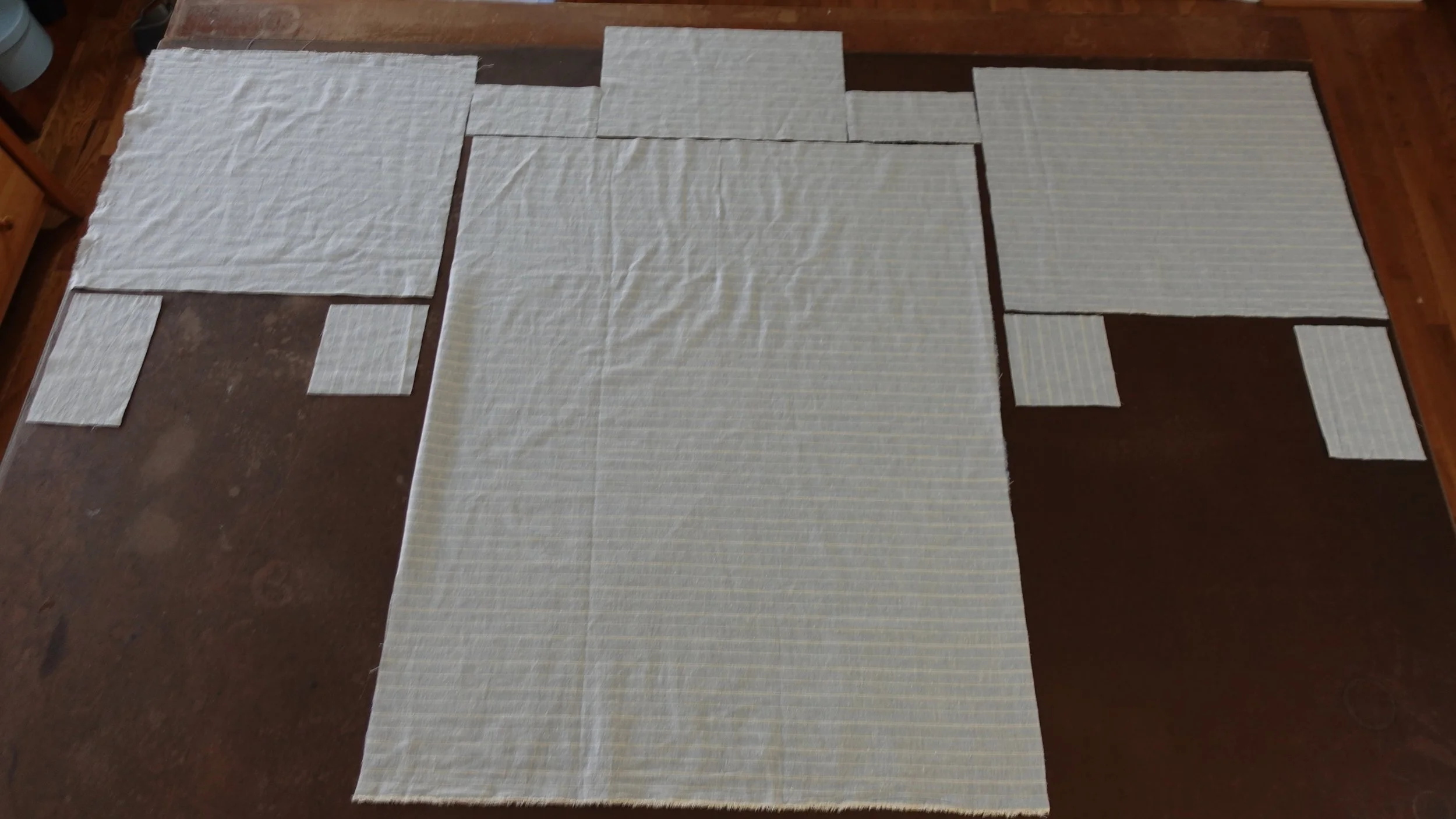

A shirt cut out on the worktable.

The opening line of the English sewing manual, The Workwoman’s Guide tells the reader to pull threads when cutting straight lines. The priority placement of this statement underscores how important and how prevalent this practice was for cutting out geometric pieces. This opening sentence also touches on a subtle but important concept: how you cut out a garment directly impacts the construction method. More specifically, how a precise pulled thread can impact hand-stitching.

I have been thinking a lot about the symbiotic relationship between pulling threads and hand-sewing. This was spurred on from my teaching of the Historic Hand-Sewn Shirt Class with Tatter Blue last year. In the past, I took it for granted I should pull a thread, it was just what I did when I cut out geometric pieces. Teaching these techniques to modern makers who had never pulled threads, underscored how integral to the process this technique is for hand-sewing on the grain line.

In this essay I return to the shirt that started this train of thought and explore the relationship of the shirt’s cut and construction.

“There must be considerable saving where the mistress of a family cuts out, or, at least, superintends the cutting out, those articles which require calculation and exactness…”

“The Ladies Economical Assistant, or The Art of Cutting Out, and Making The most useful Articles of Wearing Apparel” By A Lady, 1808. page vii.

The cost of clothing in the 18th and 19th-century Atlantic World was primarily the price of the fabric versus the labor to hand sew a garment. Knowing how to precisely cut out fabric without waste was a skill valued among consumers. As is quoted above, the cutting of shirts might have been done by a housewife, a housewife overseeing the cutting, or the job of someone disconnected from the household. On page IX in the English 1789 sewing manual, “Instructions for Cutting Out Apparel for the Poor…” author J. Walter stresses you can waste a lot of money “without consulting others, whose particular business it may have been, how to cut [shirts] out…” This distribution of labor was done by both free and enslaved workers across the Atlantic World. Up until the late 18th century these skills were taught through experience and passed down from one skilled cutter to another. In the late 18th-century, pattern books began to be published, demystify the cutting out process.

Plate 17. The Workwoman’s Guide.

The above diagram of “SHIRTS FOR THE LABOURING CLASSES” in Plate 17 in “The Workwoman’s Guide” demonstrates the math and ingenuity that went into cutting out shirts. On page 137, the author explains why these diagrams are important. The author educates the reader that “shirts for laboring men are generally made of the stout linen called shirting-linen…” this linen “should be chosen of exactly the proper width, according to the size wanted; and as it is an expensive article, especially cut to waste, six scales are drawn upon the plate for six different sizes of shirts, by which the most economical plan for cutting the shirt is seen.” The author drew these diagrams with economy in mind and also created a scale so you could cut out six of the same size shirt. The entire width of the fabric was used for the body and the rest of the yardage used to cut out collars (C), gussets (G), sleeves (S) and other smaller pieces of the shirt. The diagram shows how to layout these smaller pieces. Each of the lines represent where the cutter would remove a thread from the weave structure of the fabric to create perfectly straight lines.

“…if the shirts are made of linen, they should always be cut by a thread…”

“The Workwoman’s Guide,” By A Lady, 1838. p. 138.

It is clear why cutting precisely helps the consumer spend responsibility, but it also aids the stitcher to sew a well-stitched shirt. All the pieces are cut on the grain-line, meaning that the weave structure of the textile is on a grid. This causes the shirt to hang in a stable manner and allows the stitcher to stitch along the grain line to create beautiful details. Let us examine the cuff, felled seams and shoulder detail of the shirt to see how pulling a thread and sewing on grain affects the stitchers ability to sew precisely and beautifully.

This cuff detail really demonstrates my point. Notice how the cuff is a precise rectangle and the edges of the cuff are folded along one thread, along the grain line. The stitcher took advantage of the grain line by folding the fabric back perfectly on-grain and stitched it to the stroke gathers. The evenly spaced top-stitching is done by following one thread along the grain and counting over the threads. The buttonhole was cut in-between one thread and then stitched around the slit. The visual resonance of this cuff is created because the cutter pulled threads. The geometric nature of the cuff acts like a guide to the stitcher, making it possible to easily fold and stitch on the grain.

Above is a flat-felled seam. The left image shows the inside of the seam and the right image shows the exterior. Notice how the seam line is parallel with the grain line. You can see in the right image how the backstitches were done by following a thread across the seam and the raw edges were folded along one thread along the grain and felled down. Again— the precise pulling of threads act as a map for the stitcher to easily sew with precision.

Above is the shoulder seam. You are seeing the shoulder strap folded back on the grain line and stitched to the gathered sleeve. Notice how straight the shoulder strap is and notice the perfectly straight topstitching on the strap. While all of this sewing looks almost impossible, planning ahead and carefully pulling threads make this possible.

How a garment is cut out impacts how you sew it together. We can glean a lot from this shirt to inform historical practice, an understanding of past makers process and to be better makers in 2022. I hope this essay provided you with another way of thinking about cutting out clothing for hand-sewing, fabric cost and waste. The next time you plan to hand-sew a garment that has straight lines think about following this thread and pull a thread first.

Want to give it a try? Follow along with this tutorial or take the Hand-Sewn Napkin class. This class teaches you how to pull threads and hem with precision. It is in the Patreon Workshop library for Workshop and Silver Thimble tiers or you can find it on my site here. I will also be teaching this live on August 13th in Lexington, VA at Make It Sew VA. Sign up here!